Beyond Iron: The Overlooked Micronutrients in Pregnancy-Related Anaemia

By Edikan Uwatt; Sydani Institute for Research and Innovation

When Fatima, 28-year-old expectant mother from Northern Nigeria, visited a primary healthcare centre in her vicinity for her third antenatal check-up, she was told her haemoglobin levels were still low, despite having diligently taken her iron-folic acid tablets for months. Nkechi, 23, from Southeastern Nigeria, and Bukunmi, 25, from Southwestern Nigeria, shared similar experiences. Each of them had followed the counselling they received during antenatal sessions, taken their supplements faithfully, and tried to eat more iron-rich foods like beans and leafy greens. Yet, the diagnosis remained unchanged: anaemia.

Confused and frustrated, they each asked the nurses attending to them at antenatal clinic (ANC) the same question, “What else am I supposed to do?”. Their diets were modest but intentional. So why wasn’t it enough? These experiences reflect a broader reality faced by many pregnant women across Nigeria and similar contexts.

Anaemia in pregnancy is a widespread complication, most commonly resulting from deficiencies in iron and folate. It poses serious risks to both mother and fetus, including increased chances of maternal mortality and preterm birth [1]. During pregnancy, a woman requires approximately 1,000 to 1,200 mg of iron to support both fetal development and her own health, which is significantly more than the amount needed by non-pregnant women [2,3]. To meet the heightened iron demands during pregnancy, supplementation is often necessary alongside dietary sources [4,5].

Globally, more than 40% of pregnant women suffer from anaemia, with the majority living in low- and middle-income countries [6,7]. While iron deficiency is the most common cause, it is not the only one. Emerging research shows that other micronutrients, particularly folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin A play equally vital roles in the development and correction of anaemia during pregnancy [8,9].

Yet, these often go unnoticed. Why?

The Problem with a One-Nutrient Focus

For decades, antenatal programmes have focused on iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation, based on WHO’s long-standing guidelines. While this intervention has been beneficial, evidence now shows that it fails to address the full spectrum of micronutrient deficiencies that contribute to anaemia and poor pregnancy outcomes [10].

Anaemia is a multifactorial condition; not all cases are due to iron deficiency. Folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies, for example, cause a different type of anaemia called megaloblastic anaemia, which iron alone cannot treat [11,12]. Moreover, deficiencies in vitamin A impair the production of red blood cells and compromise the immune system, further exacerbating anaemia risks [13].

MMS vs. IFA: The Supplementation Shift

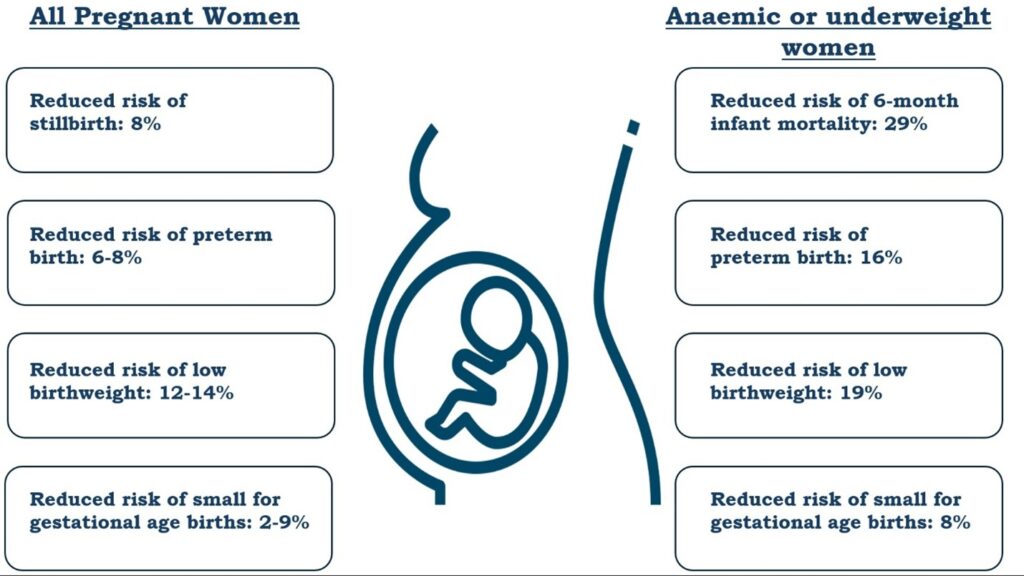

The introduction of Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMS) offers a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to maternal nutrition. Unlike iron-folic acid tablets that focus on just two nutrients, MMS provides a combination of 13 to 15 essential vitamins and minerals including iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin A, zinc, iodine, and others. These micronutrients address a broader range of nutritional deficiencies that can impact pregnancy outcomes [10]. In a 2021 meta-analysis, MMS was shown to reduce the risk of low birth weight by 12%, preterm birth by 8%, and small-for-gestational-age births by 9%, compared to IFA alone. These benefits were most pronounced in women who were undernourished or anaemic at baseline. Importantly, MMS does not increase the risk of neonatal mortality, which was a concern that once delayed its adoption [14].

What Does WHO Say Now?

In 2020, the World Health Organization updated its antenatal care guidelines, conditionally recommending the use of MMS in settings where nutritional deficiencies are widespread and antenatal care systems are strong enough to support the switch [15].

MMS in Nigeria: What’s Happening Now

Nigeria is making significant strides toward improving maternal nutrition through the adoption and rollout of Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMS) during pregnancy. The Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) has approved the use of MMS as part of its updated National Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Micronutrient Deficiencies (MNDC). This approval marks a major policy shift, positioning MMS as a key strategy to address maternal anaemia and related deficiencies more comprehensively [16].

To support this initiative, MMS has been added to Nigeria’s essential medicines list, and efforts are underway to promote local production, ensuring sustainability and cost-effectiveness in the long term. In 2024, 3 million bottles of MMS were delivered nationwide, with an additional 3 million scheduled for 2025. This distribution effort is supported by the Kirk Humanitarian Foundation, aiming to reach pregnant women across all regions of the country. Nigeria’s MMS rollout is gaining traction at the subnational level, with several states piloting and scaling implementation [17].

What’s Next for Tackling Micronutrient Deficiencies Through MMS in Nigeria

With Nigeria transitioning from Iron-Folic Acid (IFA) to Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMS) for pregnant women, there’s a major opportunity to improve maternal nutrition. But success depends on learning from past IFA implementation challenges.

Key Lessons from IFA and What to Do Differently with MMS

Transitioning from IFA to MMS faces challenges similar to those experienced with IFA, including supply chain issues, poor adherence, and weak integration into ANC services. To address these challenges, strategies should focus on strengthening supply chains, improving health worker training, enhancing community engagement, and integrating MMS into standard ANC packages [18,19].

Conclusion

Despite years of iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation, anaemia remains widespread among pregnant women in Nigeria due to multiple, often overlooked, micronutrient deficiencies. Transitioning to Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMS), which includes a broader range of essential nutrients, offers a more effective, evidence-based approach to improving maternal health outcomes. Nigeria’s adoption of MMS into national policy and antenatal care marks a significant step forward. However, success will depend on addressing past IFA implementation challenges by strengthening supply chains, training health workers, improving monitoring, and engaging communities to ensure widespread access and sustained impact.

Fig: Summary of benefits of MMS vs. IFAS on pregnant women overall and in anemic (hemoglobin <110g/L) or underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) pregnant women 14, 20, 15

References

- Benson AE, Shatzel JJ, Ryan KS, et al. The incidence, complications, and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy.EurJ Haematol. 2022;109(6):633-642. doi:10.1111/ejh.13870

- Fisher AL, Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis during pregnancy.AmJ Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1567S-1574S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.155812

- Milman N, Taylor CL, Merkel J, Brannon PM. Iron status in pregnant women and women of reproductive age in Europe.AmJ Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):1655S-1662S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.156000

- Cox A. The Effects of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Iron Supplementation in Pregnancy.Sr Honors Theses. Published online April 26, 2016. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/honors/581

- SungkarA. (PDF) The Role of Iron Adequacy for Maternal and Fetal Health.World Nutrition Journal. Published online 2021. doi:10.25220/WNJ.V05.S1.0002

- Araujo Costa E, de Paula Ayres-Silva J. Global profile of anemia during pregnancy versus country income overview: 19 years estimative (2000–2019).AnnHematol. 2023;102(8):2025-2031. doi:10.1007/s00277-023-05279-2

- Karami M,ChaleshgarM, Salari N, Akbari H, Mohammadi M. Global Prevalence of Anemia in Pregnant Women: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(7):1473-1487. doi:10.1007/s10995-022-03450-1

- Neves PAR, Castro MC, Oliveira CVR, et al. Effect of Vitamin A status during pregnancy on maternal anemia and newborn birth weight: results from a cohort study in the Western Brazilian Amazon.EurJ Nutr. 2020;59(1):45-56. doi:10.1007/s00394-018-1880-1

- Zec M,RojeD, Matovinović M, et al. Vitamin B12 Supplementation in Addition to Folic Acid and Iron Improves Hematological and Biochemical Markers in Pregnancy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Food. Published online October 13, 2020. doi:10.1089/jmf.2019.0233

- Kraemer, van Liere, Sudfeld, et al.Focusing on Multiple Micronutrient Supplements in Pregnancy: Second Edition. Sight and Life; 2023. doi:10.52439/uznq4230

- Di G, S A, C G.Anaemiain India and Its Prevalence and Multifactorial Aetiology: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2024;16(11). doi:10.3390/nu16111673

- Socha DS, DeSouza SI, Flagg A, Sekeres M, Rogers HJ. Severe megaloblastic anemia: Vitamin deficiency and other causes.Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(3):153-164. doi:10.3949/ccjm.87a.19072

- Mejia LA, Erdman Jr JW. Impact of Vitamin A Deficiency on Iron Metabolism and Anemia:A HistoricalPerspective and Research Advances. Nutr Rev. 2025;83(3):577-585. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuae183

- Keats EC,AkseerN, Thurairajah P, Cousens S, Bhutta ZA, Group the GYWNI. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation in pregnant adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Nutr Rev. 2021;80(2):141. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab004

- WHO. WHO antenatal care recommendations for a positive pregnancy experience: Nutritional interventions update: Multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy. PubMed. 2020. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32783435/

- Meshioye D. FG approves MMS for pregnant women. The Guardian Nigeria News – Nigeria and World News. January 30, 2024. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://guardian.ng/news/fg-approves-mms-for-pregnant-women/

- UNICEF. UNICEF and Partners Deliver 3 million Bottles of Multiple Micronutrient Supplements (MMS) to Boost Maternal Health in Nigeria. 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/unicef-and-partners-deliver-3-million-bottles-multiple-micronutrient-supplements-mms?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Berhanu AT, Defar A, Taye G, et al. Piloting Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation Within the Routine Antenatal Care System in Ethiopia: InsightsFromStakeholders. Matern Child Nutr. 2025;21(2):e13809. doi:10.1111/mcn.13809

- LabontéJM, Hoang MA, Panicker A, et al. Exploring factors affecting adherence to multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy in Cambodia: A qualitative analysis.Matern Child Nutr. 2025;21(1):e13745. doi:10.1111/mcn.13745

- Smith ER, Shankar AH, Wu LSF, et al. Modifiers of the effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on stillbirth, birth outcomes, and infant mortality: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 17randomisedtrials in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(11):e1090-e1100. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30371-6